Political Geography

The Navajo Nation flag illustrates the complexity of territorial sovereignty. The Navajo Nation, like other Native American tribes, is held by the US constitution to be a separate political entity, able to run its own internal affairs and with boundaries fixed (often under duress) by government-to-government treaties with the USA. At the same time, members of the Navajo Nation are also US citizens entitled to all of the corresponding rights. The precise nature of Native sovereignty is an ongoing source of tension for Native people.

photo from Flickr/dbking

Politics and Space [Link]

For the purposes of this chapter, we can define politics broadly as activity that deliberately aims at changing (or resisting changes to) how society is organized. The most visible form of politics is that carried on through the choice of governmental leaders and creation of laws. However, there are also cultural forms of politics that aim at using persuasian and social pressure to change how people live without necessarily calling for changes to the law.

Political activity is closely rooted in geography. Political actors gain bases of support from particular places, appeal to ideas about the nature of a place or landscape in order to make a case for change, and exercise power over particular places and spaces.

A core concept in modern political geography is the idea of territorial sovereignty. Territorial sovereignty is a principle that gives one government total control of a given area of land and the people that live on it. A sovereign country has a right not to be interfered with by foreign powers (Steinberg 2009, Jones and Phillips 2005). Territorial sovereignty is traditionally held to have been established in 1648 by the Peace of Westphalia that ended the Thirty Years' War in Europe. The Peace of Westphalia established the right of Catholic countries to insist that their populations be Catholic, without Protestant kings of neighboring countries being able to step in and do anything about it. And it likewise granted Protestant countries the right to establish their religion without outside Catholic interference.

We are used to seeing a map of the world in which the Earth's entire land surface is divided up into the sovereign territories of various states in contrasting colors -- around 195 of them at present, depending on how a few disputed entities such as Taiwan and Palestine are counted. However, this situation was not characteristic of much of the world until fairly recently. As European colonialism expanded, explorers and colonists imposed their definitions of sovereignty on residents of other lands. For example, when the British arrived in Australia, they found that the Aboriginal people ran their affairs according to traditional Law on the basis of consensus and deference to elders, with "Dreaming" stories connecting groups of people to certain traditional territories. This did not closely match the familiar idea of a sovereign European-style state with a government able to exercise power over a territory and conduct negotiations with other states. Thus the British declared Australia to be terra nullius -- Latin for "no man's land" -- and free for the taking by whichever sovereign state got there first (Elder 2007). The Australian government did not give recognition to indigenous claims to land until the 1992 Mabo decision by the High Court. In New Zealand, on the other hand, the hierarchical government structure and clearly defined territories of the Maori people resembled European states. Thus the British felt obligated to sign the Treaty of Waitangi with the Maori chieftains, establishing the respective rights of each group.

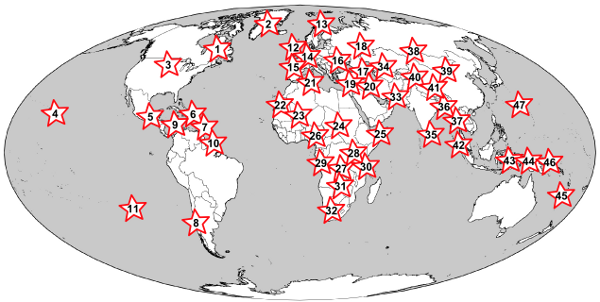

Figure 1: Sovereign states and separatist movements.

Though the earth's surface is divided up into the territories of nearly 200 sovereign states, a variety of national groups are agitating -- sometimes peacefully, sometimes violently -- for their own states. Among the more notable active nationalist separatist movements today are: 1) French-speaking Quebec, 2) Greenland/Kalaallit Nunaat, 3) Lakotah, 4) Hawaii, 5) various indigenous groups represented by the Zapatistas, 6) Puerto Rico, 7) Montserrat, 8) Mapuche, 9) Raizals, 10) French Guiana, 11) Rapa Nui, 12) Scotland, Wales, and Cornwall, 13) Sapmi, 14) Flanders and Wallonia, 15) Basques, 16) Transnistria, 17) Chechnya, Nagorno-Karabakh, Abkhazia, and South Ossetia, 18) Tatarstan, 19) Northern Cyprus, 20) Kurdistan, 21) Kabylie, 22) Western Sahara, 23) Azawad, 24) Darfur, 25) Somaliland and Puntland, 26) Biafra, Ogoni, and Southern Cameroons, 27) Katanga, 28) Batwa, 29) Cabinda, 30) Zanzibar, 31) Barotseland, 32) Volkstaat, 33) Balochistan, 34) Karakalpakstan, 35) Tamil Eelam, 36) Chittagong Hill Tracts, 37) Karen, 38) Tuva, 39) Inner Mongolia, 40) East Turkestan, 41) Tibet, 42) Aceh, 43) South Moluccas, 44) West Papua, 45) New Caledonia, 46) Bougainville, 47) Guam.

Europe is also the origin of another important political geographic concept, the nation-state. A nation is a cultural entity, consisting of a group of people who see themselves as part of a common community sharing a common way of life and a common political destiny. A state is a government institution that exercises power over its people and holds a monopoly on the use of force. A nation-state is thus a state that encompasses a single nation (Anderson 2006). Before the 1800s, it was common for large political units to be multi-ethnic. The Roman, Qin, or Ottoman state exercised power over a large territory, but they did not expect their subjects to primarily self-identify as Romans, Chinese, or Turks. But in modern times, there have been great efforts to turn states into nations and vice-versa. States have instituted policies to unite their people into a single nation. For example, 18th-century France standardized the French language based on the Paris dialect and insisted on the use of this common language throughout the country (Scott 1998). "English-only" efforts in the United States today continue this trend. Countries adopted national symbols such as flags and anthems to cultivate a spirit of community.

On the other hand, existing nations attempted to gain states that matched their national territories. Between 1945 and 2010, 125 new countries were added to the world as colonial empires were divided up into new nation-states and multiethnic countries like Yugoslavia were split into new states more closely matching national borders. A variety of national groups, from Scottish people to Kurds, are currently agitating for their own states to be carved out of the territory of existing ones (Figure 1).

Boundaries and Borderlands [Link]

Figure 2: Boundary between Arkansas and Tennessee.

The boundary between Arkansas and Tennessee was established over a century ago along what was then the center of the Mississippi River. The political boundary has remained in the same place even though the river has changed course.

data from Landsat

A classic topic of study in political geography was the nature of borders between political entities (Newman 2006, Jones 2009). Such an interest assumes, first, that political entities have clearly defined boundaries. Even in the era of territorial sovereignty, this may not be the case -- consider, for example, the border between Saudi Arabia and Yemen is undefined, largely because it runs through the desolate Rub' al Khali desert, so neither country is especially motivated to lay claim to more land. The boundary between North and South Carolina appears well-defined on paper, but because the paper definition (dating back to the 17th century) matches up with reality on the ground so poorly, the states are currently engaged in a major project to re-survey the line -- possibly determining in the process that some people are living in a different state than they had previously thought (Rose 2012). Note that the previous sentence said "determining," not "discovering" -- the boundary exists only insofar as it is recognized in practice by the governments and citizens of the respective political entities.

Boundaries are often distinguished into natural (following the course of a physical feature such as a river or ridgeline) versus artificial (drawn by humans) ones. But so-called natural boundaries are still products of human choice -- why establish that particular river, rather than this other one, as the boundary? Moreover, the political boundary may persist even after the physical feature has changed its location. Thus, the boundaries of states bordering the Mississippi River are fixed to the river's old course, though the location of its meanders have changed (Figure 2).

It is thus important to ask who has the right and the ability to define a boundary. Consider the case of Kashmir, a territory disputed between India and Pakistan. Within India, it is legally required to show Kashmir as belonging to that country. Even multinational software giant Google is subject to these laws, as can be seen by comparing how Kashmir is shown in Google's Indian and worldwide map sites (Figure 3). This means that Indians grow up always seeing Kashmir as a part of their country, of equal standing with undisputed states like Tamil Nadu or Assam. Any proposal to recognize Pakistani control over part or all of Kashmir would then provoke severe resistance from the Indian populace. Maps outside the disputant countries commonly show both boundaries, noting their disputed status. But this compromise is not neutral, as it sends a message that both claims are equally legitimate. (Imagine, for example, if Canada announced a claim to the state of New York, and maps published outside North America began showing that state as a disputed territory!)

Figure 3: Mapping Kashmir.

Indian law requires Google to show Kashmir as an undisputed part of India on its Indian site, whereas the rest of the world sees both claims shown as disputed borders.

images from google.com.in and google.com

A political boundary is not a sharp or unbridgeable divide. Boundaries are always flanked by borderlands, areas of hybridization between the two states on either side (Anzaldúa 1987). Borderlands are often sustained by the movement of people and commerce across the boundary. Attempts by states to make their boundaries more rigid, such as the United States' recent increases in security measures to stop unauthorized immigration and the drug trade, can disrupt life in the borderlands. Economic, cultural, and family ties of borderland dwellers cross the boundary. But a more rigid boundary can itself generate new ways of life at the boundary, as seen for example in the rise of human smugglers on the Mexican side helping would-be immigrants cross into the USA, and charity organizations aiming to help the recently deported.

Dividing Up Space [Link]

Political entities frequently need to divide up their own internal space in order to carry out governance. One type of internal division is administrative subdivisions, such as provinces or counties. These subdivisions create a level of governance that is more able to carry out local functions. The relationship between smaller levels of governance and larger ones can be described as either centralized or federalist. In a centralized system, such as that of the United Kingdom or France, subdivisions exist at the pleasure of the national government, and serve to carry out national policies. The national government of a centralized state always takes precedence over more local policies. In a federalist system, such as the United States or Australia, the national government exists as a federation of smaller states. These states retain some autonomy from national policies and cannot always be forced to comply with national mandates.

The Principle of subsidiarity is a common idea -- endorsed by people ranging from the Roman Catholic church to radical environmentalists to the European Union -- that holds that governance functions should be carried out at the most localized level possible (Bosnich 1996). Under the principle of subsidiarity, if a function (say, police protection) can be done by either a municipality, a province, or a country, it should be done by the municipality. The province should only do things that can't be done by municipalities, and the country should only do things that neither the municipalities nor the provinces can effectively do. Supporters of the principle of subsidiarity argue that performing functions at lower levels of government makes policies more responsive to local public opinion and local context, and gives people the freedom to move to a different area if they don't like the policies in their current place of residence. Opponents point out that local governments may be less democratically responsive (many people have more knowledge and better developed opinions about the president than about their mayor), and that consistent national policies are fairer to people in different areas and may help protect the rights of minorities.

When deciding what political entities or subdivisions should handle an issue, it is important to avoid the problem of scale mismatch (Gunderson and Holling 2001). Scale mismatch occurs when the scale at which a process occurs is different from the scale of the political unit managing it. For example, pollution of the Great lakes is a significant problem for people in the state of Michigan. But attempts by Michigan to regulate lake pollution on its own would fail. The lakes and their watershed extend far beyond the state's boundaries. No matter how strict Michigan's pollution laws, its water could still be affected by waste dumped in connected waterways in Minnesota or Illinois. For this reason, Michigan has joined seven other states in the Great Lakes Compact. Together, these states form a unit that more closely matches the scale of the ecological system.

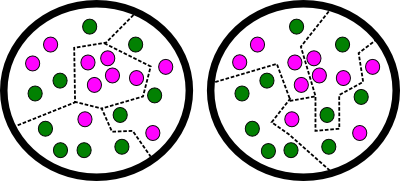

Figure 4: Gerrymandering In this hypothetical state, there are 10 voters who are committed to the Dark Green Party, and 10 voters who are committed to the Light Purple Party. In the first map, the Dark Green Party has gerrymandered the state's four congressional districts to create three safe Dark Green districts (in the east, south, and northwest), while packing the remaining Light Purple voters into the remaining central district. In the second map, with the exact same arrangement of voters, the Light Purple Party has gerrymandered itself three safe districts (northwest, northeast, and southeast), while packing the remaining Dark Green voters into the southwest district.

Another type of internal subdivision is the electoral district. In a democratic country, it is necessary to translate the votes of millions of citizens into a set of just a few hundred legislators. Some systems are non-geographical. For example, in a proportional representation system, a party gains a percentage of seats in the legislature based on the percentage of total votes it received in the entire country. Such systems can be effective at representing the preferences of interest groups that are not concentrated in specific geographical locations. On the other hand, most countries use electoral districts. The country is divided up into geographical areas, and the residents of each district select one or more legislators. This ensures that each legislator has a small, specific set of constituents that they are accountable to, and that citizens each have "their legislator" to appeal to for help. There are many principles which may be used in drawing the boundaries of electoral districts (Johnston 1999). District drawing must trade off between the various principles:

- Equal population: The democratic ideal of "one person, one vote" leads to a widespread preference for districts of equal population, so that each person's power in electing legislators is equal. This principle is implemented very strongly in the US House of Representatives, where courts have allowed very little margin for unequally-sized districts. However, note that in the US Senate, the states function as two-member electoral districts of wildly varying populations.

- Community boundaries: Because electoral districts are meant to allow local areas to have a dedicated voice in the legislature, districts often try to follow the boundaries of communities. This is essentially the principle behind the US Senate -- states are traditional communities, with Pennsylvanians thinking of themselves as a community with a common identity distinct from Marylanders, New Yorkers, etc. The Senate then gives each such community an equal number of Senators.

- Affirmative action: Minority groups may have trouble getting their voices heard and electing any representatives who are part of that minority group and will speak up for its interests. If a group makes up 20% of the population in every district, then they may nevertheless find they have 0% of the representatives because they are never a majority in any one place. To correct this, districts may be drawn to create "majority-minority" districts dominated by historically disadvantaged groups so that they can get at least one representative.

- Gerrymandering: Partisan affiliation and voting behavior tends to be very stable from election to election. It is thus possible to use fine-scale voting data from past elections to design districts that will reliably vote for a certain party. This procedure is called gerrymandering, after Elbridge Gerry, who as governor of Massachusetts drew a safe Democratic-Republican district in the suburbs of Boston that an editorial cartoonist thought looked like a salamander. Generally, if about 55% of the voters in a district are loyal to a given party, that district can be counted on to elect that party's candidate in all but the most extreme circumstances. Gerrymandering involves drawing as many just-barely-safe districts as possible for the gerrymanderer's party, while packing any leftover supporters of other parties into a smaller number of extremely safe districts. Many countries and states have instituted nonpartisan redistricting commissions to try to cut down on gerrymandering.

- Compactness: A district that is compact -- close to round, with few "bays" or "peninsulas" in its border -- is widely considered better for several reasons. It makes it easier for representatives to travel around serving constituents and campaigning. It ensures that representatives can target policies (such as the building of a new bridge) that will largely benefit their own constituents. And it serves as a protection against gerrymandering, since it is hard to gerrymander while making districts compact.

In addition to administrative subdivisions and electoral districts, governments may create other legal divisions of their territory in order to control the activities of residents. Consider, for example, laws restricting the movement of sex offenders. Aiming to protect children from predators, many municipalities have passed laws prohibiting registered sex offenders from living within certain distances of facilities such as schools and playgrounds. Depending on the size of the no-go zones, the number and type of facilities surrounded by such zones, and the layout of the town, this may leave offenders with few places to live. Cities with especially strict laws have seen the formation of concentrated sex offender colonies in the few places they are legally permitted to live (Zarrella and Oppmann 2007).

The Politics of Place [Link]

The term "politics of place" refers to a complex, two-way relationship between political activity and the identity of a place. On one hand, the right to define a place's identity is frequently one of the goals sought by political activity. On the other hand, the identity of a place can be used as a tool to advance a political cause.

At a local scale, consider a gentrifying urban neighborhood such as Mount Pleasant in Washington DC (Modan 2007). Longtime residents may attempt to define the neighborhood's identity as rough, dangerous, and oriented toward street life. This frames new arrivals as weak, effeminate, and anti-social. Longtime residents are thereby able to set themselves up as legitimate authorities whose views and leadership ought to be listened to. The newcomers, for their part, also engage in the politics of place. They envision the neighborhood as a clean, orderly, and homogeneous place. From this vision, they infer that they are the best representatives of the neighborhood's needs, while longtime residents are dangerous and irrepsonsible.

At a broader scale, consider the way candidates for national office in the United States describe the country. These descriptions serve several purposes -- they communicate to voters the candidate's vision for the country, they position certain types of Americans as "real Americans" whos views and way of life are to be favored, and they frame the candidate as an appropriate figurehead and leader for this sort of country. For example, in his speech accepting the Republican nomination for President in 2008, Mitt Romney said (Romney 2012):

Like a lot of families in a new place with no family, we found kinship with a wide circle of friends through our church. When we were new to the community it was welcoming and as the years went by, it was a joy to help others who had just moved to town or just joined our church. We had remarkably vibrant and diverse congregants from all walks of life and many who were new to America. We prayed together, our kids played together and we always stood ready to help each other out in different ways. And that's how it is in America. We look to our communities, our faiths, our families for our joy, our support, in good times and bad. It is both how we live our lives and why we live our lives. The strength and power and goodness of America has always been based on the strength and power and goodness of our communities, our families, our faiths. That is the bedrock of what makes America, America. In our best days, we can feel the vibrancy of America's communities, large and small.In this passage and elsewhere in his speech, Romney presents a vision of America as a place of close-knit communities, typically with a strong religious core, and often located in "heartland" states like Romney's home state of Michigan. By linking his biography to this vision of America, Romney worked to position himself as the natural leader of people who wanted to revive a particular ideal of the country. This was especially important for Romney, because many political commentators had predicted that voters would be suspicious of him due to his Mormon faith. Mormonism is seen by many Americans as a fringe religion practiced mostly in an odd corner of the country. But Romney successfully used the politics of place to send a message that the Mormon church fits into the ideal of supportive small-town community that can be found anywhere in the United States.

The Politics of Scale [Link]

The politics of scale is a name given to strategic choices of geographical and social scale at which a group pursues its agenda or interests (Brown and Purcell 2005).

Consider, for example, the effort to gain recognition for same-sex marriage (SSM) in the United States. Pro-SSSM efforts began by deliberately targeting the state scale. They appealed to the fact that states traditionally made marriage laws in the US's federalist system to justify their desire to have SSM decided on a state-by-state basis. State-level policymaking was advantageous because in the early days of the SSM movement, it was possible to win victories in more liberal states like Massachusetts that would not have been accepted by the national population as a whole. Advocates also believed that seeing that opponents' fears did not pan out in a few test states would convince the rest of the country to follow. As time went on, there have been increasing calls for the SSM movement to "scale up" its efforts by calling for a national policy in favor of SSM. Once again they can point to precedents legitimizing the nation as the appropriate scale, such as the Supreme Court decision in Loving v. Virginia legalizing interracial marriage. The strategic calculation now holds that due to shifts in public opinion, a national-scale victory will be easier than fighting state-by-state in conservative states like Utah.

Figure 5: Earthrise.

Photographs of the Earth from space, such as this famous photo taken by the crew of the Apollo 8 spacecraft in orbit around the Moon, helped to encourage people to think about the global scale.

photo from NASA

The politics of scale can also involve producing new scales. We are used to taking various scales as given by the nature of geographical space. But familiar scales like "national" and "global" are actually created by human activity (Marston 2000) -- someone decided that this scale was a useful one at which to carry out some plan, and so they encouraged others to think about things from this scale. Once people get used to a certain scale, they can use it for other agendas.

For example, consider the creation of the "global" scale. It is common now to think about problems having "global" significance, and to look for policies to be implemented at a "global" level to solve them. But the global scale did not exist until the age of European exploration, beginning in the late 1400s (Bartelson 2010). On one hand, human activities began to operate at a world-spanning scale, with the economic fortunes of silver mines in South America linked to the rise and fall of European powers and the economic ups and downs of China. On the other hand, people began to think in global terms. The world was increasingly represented as one abstract sphere that could be fought over, divided up, or dominated by different powers.

The environmental movement and the space program came together to further increase the salience of the "global" scale in the 1970s (Cosgrove 1994). Environmentalists insisted that pollution and biodiversity loss were threats to "the Earth" as a whole rather than to specific lands. "Scaling up" like this served to detach environmental issues from local political conflicts, to make environmentalism appear to be a more noble and "higher" cause than petty human disputes, and to call on humanity to unite for a common purpose. Astronauts' pictures of the Earth as a fragile blue marble (Figure 5) encouraged people to think about the entire planet as a unit, and provided a powerful symbol of the globe that was said to be at risk. Today, we take the "global" scale for granted.

Works Cited [Link]

Anderson, Benedict. 2006. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. Revised ed. New York: Verso.

Anzaldúa, Gloria. 1987. Borderlands/La Frontera: The New Mestiza. Second ed. San Francisco: Aunt Lute Books.

Bartelson, Jens. 2010. The social construction of globality. International Political Sociology 4: 219–235.

Bosnich, David A. 1996. The principle of subsidiarity. Religion & Liberty 6 (4).

Brown, J. Christopher, and Mark Purcell. 2005. There's nothing inherent about scale: political ecology, the local trap, and the politics of development in the Brazilian Amazon. Geoforum 36: 607-624.

Cosgrove, Denis. 1994. Contested global visions: one-world, whole-Earth, and the Apollo space photographs. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 84 (2): 270–294.

Elder, Catriona. 2007. Being Australian: Narratives of National Identity. Crows Nest NSW: Allen & Unwin.

Gunderson, Lance H., and C. S. Holling eds. 2001. Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems. Washington DC: Island Press.

Johnston, R. J. 1999. Geography, fairness, and liberal democracy. In Geography and Ethics: Journeys in a Moral Terrain, ed. J.D. Proctor and D.M. Smith, 44–58. London: Routledge.

Jones, Reece. 2009. Categories, borders and boundaries. Progress in Human Geography 33 (2): 174–189.

Jones, Rhys, and Richard Phillips. 2005. Unsettling geographical horizons: exploring premodern and non-European imperialism. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 95 (1): 141–161.

Marston, Sallie A. 2000. The social construction of scale. Progress in Human Geography 24 (2): 219-242.

Modan, Gabriella Gahlia. 2007. Turf Wars: Discourse, Diversity, and the Politics of Place. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Newman, David. 2006. The lines that continue to separate us: borders in our 'borderless' world. Progress in Human Geography 30 (2): 143–161.

Romney, Mitt. 2012. Transcript: Mitt Romney's acceptance speech. National Public Radio.

Rose, Julie. 2012. State border battle rages in Carolinas. National Public Radio, March 19.

Scott, James C. 1998. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Steinberg, Philip E. 2009. Sovereignty, territory, and the mapping of mobility: a view from the outside. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 99 (3): 467–495.

Zarrella, John and Patrick Oppmann. 2007. Florida housing sex offenders under bridge. CNN, April 5.