Development

A development worker teaches people in Tiruvannamalai, India, about contour planting. Such development projects promise to improve the livelihoods of people in poor countries, but there are many questions about what policies and programs are effective.

photo from Flickr/treesftf

A Mission to Help the World [link]

In 1949, US President Harry S Truman gave a speech outlining a new mission for the United States' engagement with the world, now that Nazism, fascism, and Japanese imperialism had been defeated:

More than half the people of the world are living in conditions approaching misery. Their food is inadequate, they are victims of disease. Their economic life is primitive and stagnant. Their poverty is a handicap and a threat both to them and to more prosperous areas. For the first time in history humanity possesses the knowledge and the skill to relieve the suffering of these people. ... I believe that we should make available to peace-loving peoples the benefits of our store of technical knowledge in order to help them realize their aspirations for a better life. ... What we envisage is a program of development based on the concepts of democractic fair dealing. ... Greater production is the key to prosperity and peace. And the key to greater production is a wider and more vigorous application of modern scientific and technical knowledge. (quoted in Peet and Hartwick 2009)

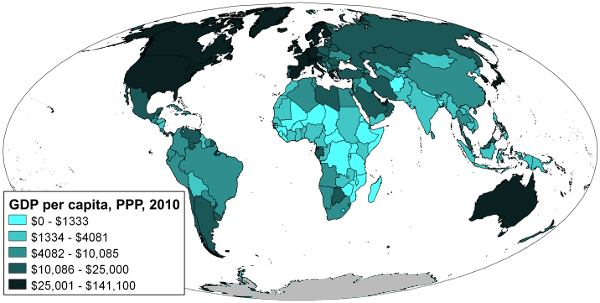

Truman's vision of the world's rich, successful countries reaching out to bring similar prosperity to the poor regions of the world has become the starting point for the field of development. Briefly, we can define development as the promotion of economic growth to bring about increased material standards of living. Figure 1 shows the level of economic wealth per capita in the various countries of the world. Despite more than 60 years of work on development, the division between rich and poor at the global scale is still apparent. It is no wonder, then, that the field of development has become highly politicized and contentious, as various schools of thought promote contrasting plans for improving the standard of living of people around the world.

Measuring Development [link]

There are several ways that we can measure development, each with their own strengths and weaknesses (Peet and Hartwick 2009).

The most commonly used measure of development is Gross Domestic Product, shown in Figure 1. Gross Domestic Product, or GDP, is a measurement of the value of all goods and services bought and sold within the country's borders. Usually we look at GDP per capita (total GDP divided by the population), since a country with more people would have more buying and selling even if the people were equally poor. It is important to remember that GDP covers only things bought and sold in the formal marketplace. Exchanges on the black market (e.g. illegal drugs) do not get factored into GDP. Nor does economic activity that doesn't involve an exchange of money. For example, if you babysit my kids, and in return I mow your lawn, nothing is added to the national GDP. However, if I pay you $10 to babysit my kids, then you pay me $10 to mow your lawn, the national GDP goes up by $20. Since much of this non-market work is done by women -- such as child care, food preparation, or cleaning -- GDP has been criticized for under-valuing women's contribution to society (Waring 1999).

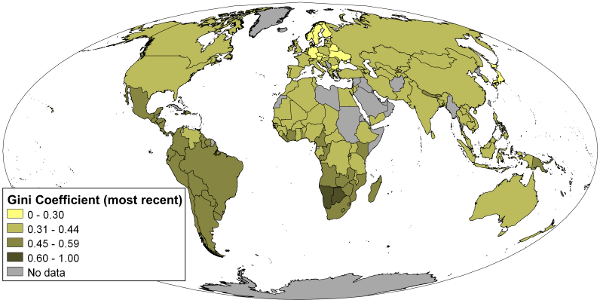

GDP per capita is an average -- total wealth divided by the number of people. But that doesn't mean each individual has that average amount of wealth. There may be millionaires and impoverished people who cancel each other out. To measure the level of economic inequality within society, we can use the Gini Coefficient, shown in Figure 2. The Gini Coefficient ranges from 0 (perfect equality -- each person has the same wealth) to 1 (perfect inequality -- one person has all of the wealth, everyone else has nothing). Many people who work in the development field believe that development strategies that spread the benefits more evenly through society, resulting in a lower Gini Coefficient, are better.

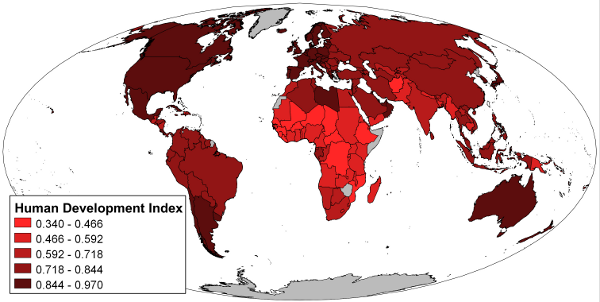

The Human Development Index, or HDI, shown in Figure 3, is based on the idea that money isn't everything. If the point of development is to raise people's standard of living, it would make sense to measure their standard of living directly, rather than simply assuming that increased wealth will improve people's lives. The HDI is made up of three components: 1) education (average years of schooling), 2) life expectancy at birth, and 3) Gross National Income (similar to GDP) per capita. HDI can theoretically range from 0 to 1.

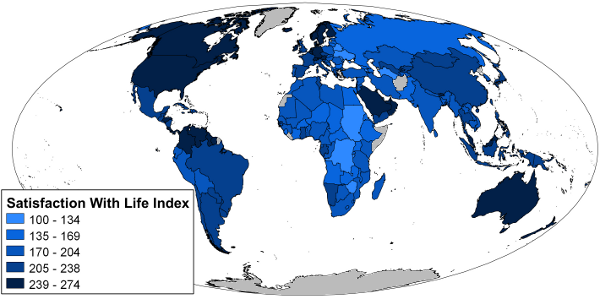

All of the measurements above are objective -- that is, researchers have decided that some measurable feature of life is what is good for people. But some people argue that we ought to let the people who are experiencing development decide for themselves whether their lives are good or bad. This rationale has led to various efforts to measure the happiness of people in various countries. There is no single widely-accepted way of computing the happiness of people in various countries, but a number of efforts -- such as the Satisfaction With Life Index (shown in Figure 4) and Gross National Happiness -- have been put together based on surveys of people around the world.

Note that all of these measurements are usually computed at the national level. However, development may be drastically different within a country. For example, within the United States, we could compare Manhattan to Jackson County, South Dakota (which lies on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation). Manhattan, being home to many investment bankers, CEOs, and other wealthy people, would have a GDP and Gini coefficient much higher than the national average, while the pervasive poverty among the Oglala Sioux people would give Jackson County a much lower GDP and Gini. As another example, in recent years China has seen big growth in its GDP and HDI, but those gains have mostly been concentrated in cities along its east coast, leaving rural western areas behind.

The Geography of Development [link]

Whichever measurement of development we choose, it is common to talk about the world as being made up of two main parts, roughly corresponding to the rich countries and the poor countries. Geographers have questioned the usefulness of bifurcating the world in this way. Look back at Figures 1-4, and note that there are often large differences between two countries in the "rich" part of the world (say, between the USA and Greece) or between two countries in the "poor" part of the world (say, between Argentina and Mali). Nevertheless, since these terms are in common use, it is important to know what they mean and what assumptions about the world are embedded in each one.

Developed world vs. developing world -- One of the most common ways of talking about these two groups of countries is to call them "developed" and "developing." The presumption here is that development is a linear process of growth that all countries go through, but some have gotten farther ahead than others. Developing countries are thus those whose development is still a work in progress, but who can be brought to the same level of development as their richer neighbors through the right set of policies.

First World vs. Third World -- The terminology of First, Second, and Third Worlds was a product of the Cold War between the US and the Soviet Union. During the Cold War, there were two competing models for development. North America, Western Europe, Japan, and Down Under (Australia and New Zealand) were committed to the capitalist model, based on private property and competition between businesses in the free market. These countries made up the First World. The Second World, made up of the Soviet Union and its allies, was committed to a communist model of development, based on a centrally planned economy in which the government dictated what, where, and how much to produce. The Third World referred to all of the other countries that had not fully committed to either the communist or capitalist path. During the Cold War, projects by the US and USSR to improve the development of Third World countries were motivated not just by an altruistic desire to help the poor, but also by the political desire to get countries to commit to the "correct" development path. With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, the communist path to development has fallen into disrepute.

Global North vs. Global South -- The terms Global North and Global South were invented by left-leaning activists who wanted a more neutral way of referring to the two groups of countries at issue. Terms like "developed" and "developing" presume the goodness of development. But these activists wished to question whether development was a good thing, at least in the form promoted by the US and USSR. So they chose directional terms to try to be more neutral. Nevertheless, these terms connote skepticism about development because of who came up with them and who typically uses them.

Center vs. periphery -- The preceding sets of terms tend to imply that development is a characteristic of a country. But according to some theories about development (such as World Systems Theory), a country's level of development is a function of its position within the global economy. That is, you can't talk about Brazil's poverty without understanding how Brazil is economically linked to richer countries like the United States. To capture this idea, we can talk about countries being in the core or the periphery of the world economy. Core countries are those that have the power to control the way global trade is carried out. The profits from global economic activity tend to flow away from peripheral countries and accrue to core countries. Talking about countries as developed or developing implies that the world's poor countries can simply catch up and be rich too. But talking in terms of core and periphery implies that the rich countries got rich by making the poor countries poor. If the US's wealth is based on exploiting Brazil, it becomes questionable whether Brazil can get rich too (unless it finds some other country to exploit).

Strategies for Development [link]

Over the 60 years since Truman's speech, a wide variety of strategies have been tried to enhance the development of the world's poorer countries. In this chapter we can only give a brief sketch of some of them.

One important distinction to keep in mind about development projects is that they can be implemented either top-down or bottom-up. A top-down project is one organized and carried out by a central government agency, often in the face of protests by citizens in the affected area. One famous example is the Sardar Sarovar dam project on the Narmada River in central India (Ramachandra 2006, Roy 1999). After India achieved independence from Britain, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru hailed the dam project as a route out of poverty for the country. The dam was to regulate flooding on the river, supply a reliable year-round source of water for farmers in the dry state of Gujarat, and provide massive amounts of cheap electricity for industry. The dam would also be a source of national pride for the country -- Nehru referred to big dams as "the temples of modern India." Yet the dam attracted a huge amount of controversy, particularly from poor people living in the areas that would be flooded by it. Through a combination of civil disobedience and new engineering analyses, opponents convinced international funders such as the World Bank to withdraw their support from the project. Nevertheless, the Supreme Court of India sided with the government, which went ahead and built the dam, completing it in 2006.

A bottom-up project is one that is put together by citizens on their own initiative. Poor people themselves can identify the needs and opportunities in their communities in order to build up local economic activity (Bebbington 1996). Bottom-up development projects may still receive aid and support from international organizations like the World Bank or Oxfam. A current fad in development programs is microcredit. The idea of microcredit is to make small loans to poor people (especially women) to enable them to start a small business such as making cheese or running a taxi service. Threats of social pressure are used to ensure that borrowers spend their loan wisely and repay it with interest. The hope of microcredit backers is that these small businesses will build the economy from the bottom up rather than relying on a few big investments like big dams, and without reliance on foreign investors to establish factories in poor countries (Grameen Bank 2010).

One of the critical questions in development is: how should a country wishing to develop integrate itself with the global economy? One theory that has been persuasive to many leaders was called import substitution. Import substitution is a policy by which trade with outsiders is restricted in order to protect and boost domestic industries (Prebisch 1959). The idea of import substitution was created in response to the observation that the international economy was often arranged in such a way as to drain wealth from the periphery and give it to core countries. Peripheral countries lacked the institutions, such as banks and factories, to compete on an even footing with the core and thus would always lose out. The obvious solution, then, was to partially withdraw from international trade. Countries practicing import substitution imposed high tariffs -- sometimes several times the item's base price -- on imports of many goods, while offering generous subsidies to domestic industries. Thus, for example, Argentine consumers' money would no longer go to the United States to buy a Ford, but instead would go to the local Siam di Tella car company. This captive market, the theory said, would give Siam di Tella some breathing room to grow its production and figure out efficient ways of making cars. Once a domestic industry had grown and become successful, it might be possible to re-open trade with foreign countries and compete on an equal footing. Import substitution had some initial success, helping countries that had inherited colonial economies focused solely on resource extraction and agriculture to quickly build up extensive industrial infrastructure. But import substitution faced problems. The government subsidies, the limited size of the domestic market, and the lack of competition with innovators around the world meant that import substitution industries became inefficient -- and consumers were stuck with inferior goods.

A nearly opposite set of policies goes by the name of neoliberalism (Gore 2000, Peck and Tickell 2002). A brief excursion into some confusing terminology is necessary here. The original definition of "liberalism" applied to the doctrines of free trade and free thought that accompanied the rise of modern capitalism in 18th and 19th century Europe. Though "liberal" has come to refer to the political left in the United States, it has stayed somewhat closer to its historical origins in Europe, where it often applies to right-wing economic policies that aim to limit government interference with the market. Neoliberalism, then, is a revival of liberal free trade policies that came about since the 1970s. The term "neoconservatism," often misused by US liberals as simply a term of abuse for conservatism, actually refers to a specific foreign policy doctrine. Neoconservatism holds that freedom can and should be spread through military force. Thus it is common for someone to be both a neoliberal and a neoconservative -- for example, former US president George W. Bush, who supported the Free Trade Area of the Americas (neoliberal) and the invasion of Iraq to bring democracy (neoconservative).

Neoliberalism holds that countries will develop faster if they reduce the government's interference in the global free market. In some cases, countries adopted neoliberal policies freely. In other cases, countries had accumulated huge debts (often taken on to finance import substitution policies that ultimately were unable to pay off the investment). These indebted countries could be forced by creditors such as the International Monetary Fund or World Bank to institute neoliberal policies, as a condition for getting better terms on their loan. This forced neoliberalism is often referred to as "structural adjustment," as the creditors believed that fixing the debtor countries' economic structure would make them more prosperous and thus more able to pay back their loans. The specific policies instituted under a neoliberal system included a reduction in tariffs on imports, lifting restrictions on foreign investment, reducing taxes, reducing government services like education and health care, and eliminating subsidies to industries.

Neoliberalism has led to higher rates of overall economic growth than import substitution. At the same time, it has also greatly increased economic inequality within countries, so the benefits do not flow to all citizens. The poor often find themselves losing access to natural resources as they are claimed by private companies to fuel economic growth that never trickles down. For this reason, many countries have seen left-wing populist leaders (such as Bolivia's Evo Morales) arise and oppose the neoliberal system. Whether these leaders can create a successful alternative model of development remains to be seen.

The cycle of colonialism, import substitution, indebtedness, neoliberalism, and anti-neoliberal populism applies well to most of Latin America, Africa, and southern Asia. These countries have seen an overall development trajectory that stagnated in the 1980s but has been growing rapidly in the 2000s. Yet these countries still remain part of the periphery or developing world. On the other hand, several countries -- notably Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore -- have made a dramatic leap from being among the world's least developed to among the most developed in the half century since Truman's speech.

The model followed by these countries, sometimes called the "Asian miracle," combines the focus on exports of neoliberalism with the government subsidies of import substitution (Lee 1999). In these countries, the government picks certain "winning" industries or companies and establishes policies to favor their growth. Manufacturing and high-tech industries were chosen as the "winners," since a focus on raw material production had the potential to lock the country into a neo-colonial relationship with richer countries who would import their resources then sell them back the finished manufactured goods. Meanwhile, manufacturing was attractive because these countries had abundant supplies of cheap, low-skilled labor as compared to older manufacturing centers in the world economic core. The policies instituted by these countries may include tariffs on imports of competing goods, direct or indirect (e.g. through infrastructure investment) subsidies to the industries, government planning and oversight of companies' decision-making, regulation of competition, and aid in marketing. Their products are then aggressively exported to other parts of the world, bringing in substantial wealth that can be reinvested.

While the Asian miracle countries experienced massive economic growth, they hit a rocky patch in the 1990s. Government intervention in the "winning" industries and a lack of competitive pressure had tended to make them inflexible, inefficient, and dependent on corrupt relationships with government officials. These longer-term structural problems combined with the bursting of investment bubbles that had been inflated by the newly earned cash. The result was a stagnation of growth in these countries. At the same time, though, a second generation of east and southeast Asian countries such as China and Malaysia have begun to try to follow in their neighbors' footsteps.

Critiques of Development [link]

The geographical literature is littered with examples of specific development interventions that have gone wrong, destroying local environments and communities. But some scholars and activists have gone further, questioning whether development -- particularly development sponsored and funded by external players -- is really such a great thing to be aiming for at all. While these people are in favor of improving the standard of living of the world's poor, they don't think this can be done within the framework of "development." Looking to economic growth as a solution, they say, can only bring problems.

One common criticism of development is that it undermines local communities and traditions (Shiva 2005). Development usually requires participation in the global market economy. This means that local subsistence production and handicrafts will be out-competed by efficient major companies. This also brings a rapid diffusion of new products, media, and values into regions that undergo development. Local cultural traditions can be replaced by the mass-produced culture of the global market.

Development can also expose people to greater risks due to being more closely linked into the global economy (Bobrow-Strain 2001). Back in the chapter on population, we discussed the massive spikes in corn prices in Mexico that were due to changes in demand (specifically the boom in ethanol production) in the United States. Mexican corn farmers and corn eaters found themselves at the mercy of market conditions originating far away, and which they had no control over. All around the world, people who have gotten involved in economic enterprises that promise development have been taken on roller-coaster rides as global prices go up and down.

If the thinkers who talk about the world in terms of core and periphery are right, then development may simply drain a country's wealth to the rich regions of the world (Kirsch 2008). Developing countries may receive short-term economic boosts at the cost of losing control of their land and resources to foreign companies.

Finally, there is concern that development may be environmentally unsustainable (Sachs 2002). We will discuss this issue in more detail in the chapter on sustainable development. For now, we can simply point out that increasing economic activity tends to use up more resources, and produce more waste. There are serious questions about whether the global environment could handle the spread of a US-style economy to all parts of the world. The local traditions mentioned in the first criticism of development were often calibrated through long practice to maintain the quality of the environment, but they are lost or rendered useless when development takes place.

Works Cited [link]

Grameen Bank. 2010. What is microcredit?

Peck, Jamie, and Adam Tickell. 2002. Neoliberalizing space. Antipode 34: 381-404.

Ramachandra, Komala. 2006. Sardar Sarovar: An experience retained? Harvard Human Rights Journal 19: 275-281.