Disability

This broad, unobstructed sidewalk is an environment compatible with a variety of ways of getting around, including both visual navigation and finding one's way with a cane like these two blind individuals.

photo from Flickr/SpecialKRB

Identity [link]

This is the first of three chapters dealing with the concept of identity (Brubaker and Cooper 2000). Identity answers some of the fundamental human questions -- Who am I? What is my place in society and the world? How should I interact with others? As social scientists, we are primarily interested in identities that place people in larger groups -- for example, racial or ethnic categories. The point is not that a person is no more than their group memberships, but rather that group memberships are important because they affect the lives of large numbers of people.

Identity is often explained in terms of an intersection of numerous axes of difference. An axis of difference is any characteristic by which people are distinguished into different groups and thus different identities. Race, class, gender, and disability are some of the most salient identities in 21st-century U.S. culture. Thus, I would be giving you a significant -- though hardly complete -- picture of who I am and how my life goes if I told you that I was a white, middle-class, cisgender man with no significant disabilities. Different axes of difference are salient in different societies. For example, caste -- a system of hereditary occupational and status categories -- is an axis of difference that is of great importance in India. Despite the outlawing of caste discrimination in the Indian constitution, people find that their opportunities in life are shaped to a substantial degree by the values and expectations they internalize while being raised as a member of a particular caste, and by the way they are treated by others on the basis of their caste. But in the United States, outside of some Indian immigrant communities, caste plays no role. The vast majority of Americans have no caste, and do not relate to others on the basis of those people's caste. As another example, race is an extremely important axis of difference in 21st-century US culture. It matters very much to a person's sense of themselves and relations with others. But as we will learn in the next chapter, race is a relatively recent invention. In other times and places, such as Egypt during the time of the Pharaohs, race as we understand it today was not recognized as an axis of difference. Lighter-skinned and darker-skinned inhabitants of the Nile valley mixed freely without any expectation that skin color ought to make a difference to someone's place in society (Draper 2008).

Axes of difference often function as axes of inequality. Any time people are distinguished into two or more groups, there is an opportunity for one of those groups to be dominant over others. Thus, to study gender (for example) is not just to study the differences between men's and women's lives, but also to study the ways that a relative advantage in society accrues to men. Attempts to ignore or erase difference, on the other hand, can also produce inequality, as some people won't measure up to whatever standard is set as the one everyone should be like.

Inequality is typically enforced by some of the same processes in all axes of difference (Pharr 1988, Young 1990). As we discuss several salient axes of difference (disability, race/ethnicity, gender, sexuality, and age) in this and coming chapters, think about how each of these processes shapes the geography of identity, and how the geography of identity supports or hinders each of these processes.

One important process by which difference becomes inequality is the habit of treating people from the dominant group as the unmarked norm, while people from other groups are departures from the norm. For example, in the 21st century United States, heterosexuality is an unmarked norm, whereas other sexual orientations are treated as departures from it. This means that when we meet a new person, we implicitly assume that they are heterosexual. We assume that interactions between opposite-sex people (particularly if they're both single and of similar ages) automatically contain the potential for sexual or romantic involvement, whereas same-sex interactions are not treated that way. Children get asked about their mother and father, even if they were actually raised by a same-sex couple. Sometimes this use of an unmarked norm is unintentional, and the questioner in our above example may be genuinely apologetic if it turns out the child had two mothers. Other times the unmarked norm is a deliberate strategy to value one type of identity -- think, for example, of the people who insist that the default greeting in December should be "Merry Christmas," rather than the more religion-neutral "Happy Holidays," because they believe the United States is a Christian country where Christian beliefs and practices should be favored. But even when it is unintentional, treating one type of person as an unmarked norm tends to reinforce inequality along the relevant axis of difference.

Inequalities are upheld and justified by promotion of ideology (Seliger 1977). Ideology is a way of thinking that 1) treats the interests and perspective of one group of people as representative of all humanity, and 2) makes the dominance of that group appear natural or normal. For example, archaeologists (most of whom are white) studying Native American remains frequently claim that their studies produce knowledge for the good of all of humanity. But many Native Americans reply that esoteric archaeological studies are of interest only to a small group of people, and that they would benefit much more from being able to re-bury their ancestors in accordance with their traditions (Danielson 2003). One of the important tasks of social science is to cut through ideology. We can find out that certain types of people have interests that are not well-served by the usual ways of doing things. And we can discover that society could be organized in different ways than it is -- there is nothing "natural" about male dominance, the nation-state, the free market, etc. Nevertheless, social science also has a long history of reinforcing ideology. Members of dominant groups claim the right and ability to define other groups, while denying those groups the right to speak for themselves (Said 1978).

Both the establishment of unmarked norms and the promotion of ideology are backed up by structural power (sometimes also called "institutionalized power"). It is common to think of discrimination as a matter of individual bad acts, done by people with hate in their hearts. While these kinds of acts do occur, they are not sufficient to explain the persistence of inequality. Inequality is a social structure in the sense we discussed in our chapter on culture -- a pattern of behavior by many people, which serves to make it convenient and rational for other people to continue behaving that way.

Structural power enables the culture to automatically punish anyone (including potentially members of the dominant group!) who do not comply with the maintenance of the structure. The punishments can range from a loss of respect, to economic consequences, to physical violence. Luckily, structures are never perfect or complete. There are always gaps or inconsistencies that create opportunities for people to push to change the structures into forms that are better. Remember that we can't do away with social structures (societies couldn't function without them), but we can try to choose better structures.

Consider an example from my short career as a substitute teacher prior to becoming a professor. One day I was assigned to cover a 9th grade class in which a sex education lesson was being given by a representative from the county health department. To illustrate the importance of being willing to say no to sex, and of respecting other people's "no," she gave a hypothetical scenario in which a boy said no to his girlfriend's sexual advances. The class burst out laughing, as they found it absurd that a boy would ever say no to sex. The myth that men always want sex makes up part of our society's structure of gender inequality -- it works to shame women into taking on the burden of taming and regulating sexuality, to give men an excuse when they commit sexual assault or adultery, and to frame gay men as sexual predators. No one student was responsible for perpetuating this myth in that class. Instead, each student saw that it was necessary to go along with the laughter, and to ridicule anyone who didn't, lest they themselves be ridiculed.

A final general consideration with respect to identity is intersectionality. Intersectionality means that a person's identity along one axis of difference may vary depending on their position on other axes of difference (Crenshaw 1994). This may be most easily illustrated with some examples. We can examine gender in general, and see some characteristics that are common to the identity of all women. But women's experiences as women can be very different depending on other aspects of their identity. Thus a woman who is not disabled will often experience being treated as a sexual object -- men will ogle her and feel entitled to her sexual and romantic attentions even when she does not welcome them. On the other hand, many women with disabilities face the opposite concern -- they are de-sexualized, as people presume that a disabled woman cannot engage in, and must not be interested in, sex and romance (Asch and Fine 1997). Here the axes of disability and gender intersect so that a person's experience is more than just the sum of their gender plus their disability status.

The Social Model of Disability [link]

The first axis of difference we will explore is disability. Disability is a broad category of ways that people's lives are affected by ways that their bodies and minds vary from their culture's ideal or norm.

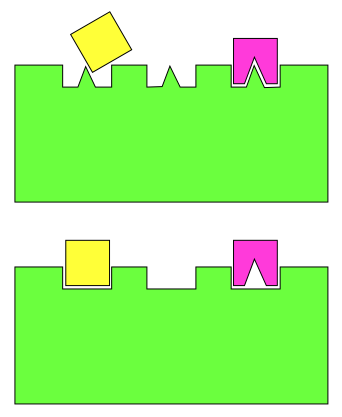

Figure 1: The social model of disability. In the top diagram, the environment (green block) has been designed with the assumption that all blocks have a V-shaped gap like the right-hand block, so the solid block on the left is not accommodated. The left block's lack of a gap would be considered its impairment, while the awkward angle it is laying at is the disability. In the lower diagram, the environment is designed to accommodate both types of blocks. The left block still has its impairment, but that no longer causes a disability.

based on Oliver 1996

The most common way of thinking about disability -- so common in modern US society that we simply take it for granted -- is called the medical model. Under the medical model, disabilities are thought of as flaws or problems in the disabled person. The problems faced by disabled people in living their lives are considered to be due to their inability to match up to what normal people can do. The medical model encourages us to think that the best solution to disability is to cure it -- help blind people see, help paraplegics walk, help autistic people understand social interaction in the normal way. New surgeries and genetic therapies are held out as giving hope to lives that would otherwise be burdened by their flaws.

In contrast, geographers studying disability argue that we should think in terms of what is called the social model of disability, illustrated in Figure 1. The social model of disability holds that the problems faced by people with disabilities are the result of a mismatch between the person and their environment (Oliver 1996). Our cultural landscapes are structured with certain types of people in mind, treating those people -- people who can see, and walk on two feet, and don't panic in large crowds, for example -- as an unmarked norm. Anyone who varies from that norm will have problems getting by in an environment that does not accommodate their body and/or mind. If we think in this way, then changing the environment can be as relevant a solution to disability as "curing" the way the person differs from the norm. Under the social model, we use the term "impairment" to refer to the way a person's body or mind differs from the norm, and "disability" to refer to the difficulties experienced due to the mismatch between the environment and the impaired person's abilities.

For example, the medical model would say that a blind person is disabled because they lack the ability to see. The social model would say that a blind person is disabled because they lack the ability to see (the impairment), yet live in an environment where it is necessary to see in order to get by. If the blind person were to live in a different sort of environment -- say, one where everything was as easily available in Braille as in print -- they would not be disabled, because they could get by just as easily as a person who can see.

The Geography of Disability [link]

Armed with the social model of disability, which asks us to focus on how the environment does or does not accommodate certain types of people, we can explore the geography of disability. The first question to ask is, simply, what spaces are accessible to different kinds of people?

The easiest examples have to do with cases in which the physical structure of the space is incompatible with certain impairments. A wheeled vehicle can't navigate certain types of terrain, and so a lack of curb cuts, ramps, and elevators can greatly inhibit the movements of a wheelchair. A deaf person may be able to physically enter a movie theater (assuming they have some way of ordering their ticket from a box office attendant who likely does not know sign language), but if the movie is not closed captioned, then it's pointless to go there. Depending on how important a certain space is to being able to get along in life within the culture in question, this can have a major impact on a disabled person's life -- as for example when the non-accommodating space is a workplace (Hall 1999).

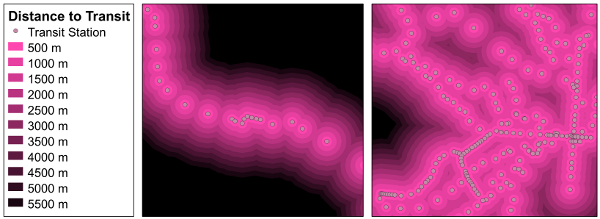

Figure 2: Distance to the nearest subway or light rail station, St. Louis and Philadelphia. These maps are merely indicative, as they do not account for the difficulty of moving around outside the station, or the presence of other public transportation such as bus routes.

data from National Transportation Atlas

The geography of disability may also manifest at a wider scale. Consider Figure 2, which shows the distance to the nearest transit station in Philadelphia and St. Louis, two similarly-sized urban areas. Many impairments, e.g. paraplegia or epilepsy, make it difficult or impossible for a person to get around by private automobile. From the maps, it is clear that a person who is thus dependent on public transportation is going to find much more of the Philadelphia area accessible than they would in St. Louis. We could then go on to ask what kind of consequences that has for the lives of people with disabilities in these cities -- what kind of amenities (housing, stores, service agencies) are located in the less accessible parts of the city? We can also ask why the landscape is set up in such a way. A huge variety of policy measures either directly (through construction funding) or indirectly (through zoning requirements) push a city toward a more transit-focused or more car-focused landscape.

Further, just because a space is physically accessible to a person doesn't mean their experience of it will be equal to the experience of anyone else. Often physically accessible spaces may be socially unwelcoming to people whose minds and bodies do not fit the social norm. For example, some impairments lead people to have an unusual gait, perhaps swaying or jerking more than a person without the impairment would. When people with such impairments go out in public, they report a range of hostile reactions from other people sharing the space with them -- from stares, to being ignored in favor of their non-disabled companions, to condescension, to being accused of drunkenness. This places a burden on the disabled person in using the public space (Hansen and Philo 2007).

Finally, we may ask how geographical circumstances and processes can create the very impairments that may then be poorly accommodated by a disabling environment. Certainly many impairments can be treated as exogenous variables -- people with certain bodily or mental variations just show up to a world that hasn't been constructed with them in mind. But other times, there are social causes of those variations. For example, a variety of health conditions, from cancer to lead poisoning, can result from pre- or post-birth exposure to toxins in the environment (which are, in turn, a result of society's choices about how to organize its economy and residential patterns). Wars and their aftermath (e.g. land mines) can produce impairments like loss of limbs or post-traumatic stress disorder. And ageing populations as a result of the demographic transition may lead to a wider prevalence of difficulty walking, limited vision, and other impairments that can arise in old age. On the other side, changes in social conditions may reduce the prevalence of certain impairments, as has happened in the industrialized world with the reduction in the effects of lead poisoning and polio over the last few decades. A shift in the balance of impairments in a society creates challenges for the society to adjust its social and physical environment, or else risk excluding more of its people from equal participation in life.

Works Cited [link]

Asch, Adrienne, and Michelle Fine. 1997. Nurturance, sexuality, and women with disabilities. In Disability Studies Reader, ed. Leonard J. Davis, 241-259. London: Routledge.

Brubaker, Rogers, and Frederick Cooper. 2000. Beyond "identity". Theory and Society 29: 1-47.

Crenshaw, Kimberlé Williams. 1994. Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. In The Public Nature of Private Violence, ed. Martha Albertson Fineman and Rixanne Mykitiuk, 93-118. New York: Routledge.

Danielson, Stentor. 2003. Stereotypes, trust, and Kennewick Man. Different Voices, Spring.

Draper, Robert. 2008. Black pharaohs. National Geographic, February: 34-59.

Hall, Edward. 1999. Workspaces: refiguring the disability-employment debate. In Mind and Body Spaces: Geographies of Illness, Impairment, and Disability, ed. Ruth Butler and Hester Parr, 138-154. London: Routledge.

Hansen, Nancy, and Chris Philo. 2007. The normality of doing things differently: bodies, spaces and disability geography. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 98 (4): 493-506.

Oliver, Michael. 1996. Understanding Disability: From Theory to Practice. New York: Palgrave.

Pharr, Suzanne. 1988. The common elements of oppressions. In Homophobia: A Weapon of Sexism. Inverness, CA: Chardon Press, p. 52-64.

Said, Edward W. 1978. Orientalism. New York: Pantheon Books.

Seliger, Martin. 1977. The Marxist Conception of Ideology: A Critical Essay. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Young, Iris Marion. 1990. Justice and the Politics of Difference. Princeton: Princeton University Press.