Environmental Perception

West African villages like this one, Siguiri in Guinea, have been the scene of significant clashes between perceptions of the environment. European explorers and rulers assumed that the mix of trees, pasture, and barren ground must mean that this region was once entirely forested, but human overuse had degraded the environment to grassland or bare ground in places. Policies were put in place to limit villagers' animal herds and gathering of firewood to encourage the forest to regrow. But research has since shown that the perception of the land as degraded was based on a false assumption of natural climax vegetation that can only be degraded by human activity. In fact, this whole area would be treeless in the absence of humans. Fertilization by human activity was what enabled these trees to grow (Fairhead and Leach 1995).

photo from Flickr/rogoyski

Perception is an Active Process [link]

Take a look at the forest depicted in Figure 1. What do you see? Do you see a beautiful landscape to be appreciated? A harsh and dangerous wilderness? Evidence of the might and majesty of the Creator? A resource to be exploited for profit? All of these have been important ways of thinking about forests -- and none of them is the "correct" way to look at the forest. There is no scientific proof that the forest really is a resource rather than a place of beauty. However, different ways of looking at the forest will lead to different ways of interacting with it. A dangerous wilderness is likely to be cleared and tamed, while evidence of the Creator would be preserved for future generations. For this reason, it is important to think about how people form different perceptions of their environment.

We commonly think of perception of the environment as a passive process. People just sit back and absorb data from the environment. Under this way of thinking, culture acts as a distortion. There is one right way to think about the environment, but culture can bias or distort your understanding. We can call this belief in one correct perception of the environment objectivism. But the idea of perception as passive and culture as distortion is inconsistent with what geographers and anthropologists have found about how people from different cultures interact with the world (Ingold 2000). A better way of thinking about environmental perception is that perception is active. People seek out information about their environment based on what they need to know for their current projects or interests. In this way of thinking, culture acts as a guide or roadmap. The beliefs and behaviors that make up culture tell you what kind of things you are likely to encounter in the environment, how you can find them, and what you can do with them. Without this culture, the environment would just be an incomprehensible mass of sensations. Some people have taken this theory of active perception as justification for being a relativist. Relativism is the opposite of objectivism -- it's the belief that no way of perceiving the environment is any better than any other. While relativism may be appealing, it is also a poor way to think about the diversity of perceptions of the environment. Pragmatism provides an alternative to either objectivism or relativism. Pragmatism says that we should judge perceptions of the environment according to how useful they are for people in getting along with their lives. There is a real environment out there (as objectivism says), and so some perceptions will lead you to ruin. But no one perception necessarily works best for every situation. Instead of there being one right way to perceive the environment, there may be multiple ways of perceiving it, each of which may be more or less useful for a given person's projects and interests (Dewey 1958).

Grid-Group Cultural Theory [link]

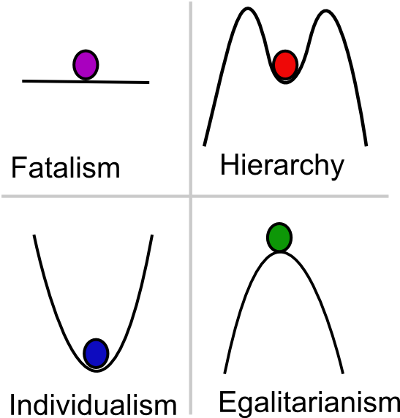

To understand how different people come to different perceptions of the environment, we can use the framework of Grid-Group Cultural Theory. GGCT was developed by anthropologist Mary Douglas, who noticed that many groups -- from the Lele tribe in what's now the Democratic Republic of Congo to environmentalists in the United States -- followed a few similar patterns of social organization and environmental perception. She and her followers systematized these similarities into a scheme of four basic worldviews: Individualism, Fatalism, Hierarchy, and Egalitarianism (Thompson et al 1990, Douglas and Ney 1998). (The name "Grid-Group Cultural Theory" comes from the way Douglas constructed the four basic worldviews out of underlying variables she called "grid" and "group" -- but to keep this chapter short, we won't be discussing grid and group further.)

Figure 2: Grid-Group Cultural Theory's four worldviews. Each worldview is represented as a surface with a ball resting on it. Individualism's surface is curved like a cup, so no matter how hard it is shaken (i.e. how much the environment is disturbed), the ball will come back to rest at the bottom. Fatalism's surface is flat, meaning a little bump could send the ball rolling unpredictably in any direction. Hierarchy's surface is a cup with a low lip, meaning that any disturbance that exceeds that limit will cause the ball to fall out and roll away. Egalitarianism's surface is a peak with the ball balanced precariously on top, so any disturbance could cause catastrophe.

based on Thompson et al. 1990

Individualism is a worldview based on freedom for individuals to compete for wealth and status. Individualists believe that as long as no artificial restraints are placed on anyone, then the marketplace will allow the best and most deserving to rise to the top. People who fall behind have only themselves to blame. Individualists tend to see the environment as resilient and robust. Nature will take care of itself and bounce back from whatever people do to it. Therefore, people can be free to exploit it in order to get ahead -- there is no need for any restrictions on freedom in order to promote conservation.

Fatalism is a worldview based on dealing with luck. Fatalists do not feel in control of their own fortunes. Both social and environmental forces are unpredictable and uncontrollable. From a fatalist perspective, all that you can do is to enjoy your good luck while it lasts, and hunker down and try to survive when your luck turns bad. Any attempt to make long-term plans or to achieve social change is a waste of effort.

Hierarchy is a culture based on the promotion of order. Hierarchs seek a society in which everyone knows their place in the overall scheme of things, and people are ranked in order of holiness, expertise, seniority, or some other organizing principle. In this system, people lower on the chain have a duty to obey, while those in positions of authority have a duty to look out for the best interests of all of the people below them. Hierarchs see the world as having definite limits to how people can legitimately interact with it. It's fine to use resources, but only up to a certain limit. It is necessary to have experts, such as priests or scientists, who can determine where these limits lie, and then create and enforce rules so that nobody transgresses them.

Egalitarianism is a culture based on equality and solidarity. Egalitarians aim to live by a creed of sharing and brotherhood/sisterhood, in which no one person has authority or power over any other. The egalitarian way of life depends on shared commitment by all members -- everyone has to go "all in" for the good of the group. Egalitarians tend to see the environment as extremely fragile. Fears of a catastrophic collapse – whether it be Armageddon or nuclear meltdown -- help to keep up people's enthusiasm for focusing on the good of the group and avoiding any search for individual advancement.

To illustrate how these worldviews work in practice, we can consider applying them to the issue of climate change (Douglas et al. 2003). An individualist would tend to be skeptical that climate change is occurring. After all, how can human activity mess up something as big and resilient as the global climate system? Perhaps people who warn of climate change are just coming up with excuses to restrict the freedom of competition because they're afraid of losing. If an individualist does become convinced of the reality of climate change, they will tend to trust the market to fix things. Environmental "problems" are really just opportunities for some entrepreneur to make a profit by figuring out a solution to sell. The worst thing that we can do is to make rules that inhibit the flexibility and creativity of competitive individuals.

A fatalist would distrust any predictions of the likely consequences of climate change. It would be easy for some unexpected catastrophe -- or some unexpected boon -- to arise. A fatalist approach to climate change would focus on adaptation. If we think about ways that we can ride out a crisis, it will serve us well whatever happens. And if it doesn't, then fate has just dealt us a bad hand.

A hierarch would focus on ways to regulate and control climate change. Hierarchs would want to scientifically determine the critical threshold at which climate change becomes irreversible and catastrophic -- is it 450 parts per million of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere? 350 parts per million? Once this is determined, rules can be made that will ensure that nobody transgresses the threshold. This might come in the form, for example, of emissions permits that restrict the total emissions to under a certain amount. A hierarch's biggest fear is disorder -- the anarchy of the market in which people have no respect for the rules that ought to limit their behavior.

An egalitarian sees climate change as confirmation that the environment is fundamentally fragile. Improper behavior aimed at aggrandizing the individual or society has put us out of balance with nature, and now we are getting our comeuppance. The egalitarian solution lies in adopting a simple way of life. Any interference with nature's balance is potentially dangerous, so we should be aiming to move quickly to a zero-carbon society rather than permitting some acceptable amount of emissions.

By now, you are probably thinking that these four worldviews are simplistic. This is correct. The four worldviews of Grid-Group Cultural Theory represent four tendencies that people fall into when trying to put together a consistent outlook that will motivate a clear plan of action. But the world is far more complex than any of these worldviews can account for. In fact, the world is more complex than any one worldview can account for. Thus, it would be wrong for an objectivist to try to argue that one GGCT worldview is the one right worldview.

However, it would also be wrong for a relativist to argue that the four worldviews are all equally good, and thus it doesn't matter how we perceive the world. Grid-Group Cultural Theory is a pragmatist theory. It holds that each worldview captures an important part of the picture. Problems and solutions that one worldview misses can be picked up by the others. To have a truly functional society, it is necessary to have representatives of all four worldviews giving their contributions. In any one situation, one worldview may be the closest to the truth of how the world works, and thus following that worldview's recommendations will lead to success. But this nice match never lasts forever. Eventually, the environment will surprise you. It then becomes necessary to shift into a different worldview in order to get a grip on what the environment is doing and figure out how you should respond (Thompson 1997).

Consider the climate change example in the context of a pragmatist view of environmental perception. All four worldviews have something important to contribute. Individualists warn us not to impose regulations without due cause, because they can stifle the ability of societies to solve their own problems. Fatalists remind us that no prediction can ever be completely accurate, and so we should be prepared to encounter unexpected luck. Hierarchs encourage us to seek better information and trust reliable experts. And egalitarians are quick to raise awareness of potential catastrophes that any given policy may lead to.

Discourses About the Environment [link]

Various perceptions about the environment get spread through discourses. A discourse is a shared way of thinking or speaking about an issue. A discourse promotes a certain worldview and gives it a specific application to certain cases (Dryzek and Berejikian 1993). Discourses usually take the form of narratives (Roe 1994). They tell a story, with characters and settings, about how the world got the way it is and how we should shape our future. It may be easy to poke holes in a prevailing discourse, but it's usually necessary to offer a competing discourse in order to change people's minds.

Discourses are a common way that ideology is promoted. If people get so used to thinking in a certain way that they have trouble imagining the world in a different way, then they might unknowingly treat one group's interests as identical to the interests of everyone. But discourses can also help strike back against inequality. They can give people resisting an ideology an alternative story to help them see how their cause is right.

Discourses are unavoidable in human-environment interaction. We need to have some way of talking about our environment in order to coordinate our activities with others and figure out what we should be doing. But discourses can become entrenched, so that they continue to guide our behavior even when they have little basis in how the world works and may even make things worse (Fairhead and Leach 1995).

Discourses about the environment can serve many purposes. Sometimes arguments over how the environment works are just proxy battles for a larger political fight. An example, wildfire policy in Australia (Pyne 1991, Collins 2006), can serve to illustrate how discourses become established and are challenged.

Figure 3: Aftermath of Black Saturday bushfires, Kinglake, VIC. The fire that destroyed this home, along with many others, sparked several competing discourses. One placed the blame on environmental regulations that restricted fuel reduction burning, while another asked whether human interference with nature -- through building in unsuitable spots and making extreme fire weather worse through climate change -- might be to blame.

photo from Flickr/Sascha Grant

In Australia, Aboriginal people developed a discourse that said fire is a crucial part of how humans should relate to the land. While the specifics of the discourse varied between ecosystems and cultural groups, the basic tenets were similar. Deliberately lit fire was a practical tool for encouraging the growth of desirable plants, chasing game, and reducing the risks of big fires. Moreover, fire was also part of the stewardship responsibility people had -- land that had not been burned in some time was seen as abandoned and messy, in need of someone to "clean up country." Fire thus helped to maintain the Aboriginal way of life in which each individual, clan, and tribe had particular responsibility for caring for certain territories.

When British settlers first arrived in Australia, they brought with them a discourse about fire that had made sense in the wet, heavily populated regions of western Europe. To them, fire was a dangerous and destructive force, which destroyed precious resources. Anyone who deliberately lit fires, like the Aborigines did, was an irresponsible manager of the land. The British government, and later the independent Australian government, set up programs to eradicate fire from the land. It was believed that if fire was suppressed long enough, the ecosystem would shift into a different composition of plants and become fire-resistant. This shift would aid the larger British-Australian project of making efficient, intensive use of Australia's resources.

The anti-fire ideology of the British-Australian elites turned out to be a failure by the pragmatist criterion of enabling successful life in the environment. A series of major fires, most notably the "Black Friday" fires of 1939, convinced Australia's leaders that a 180-degree change in fire policy was needed. Instead of trying to suppress fires, the new discourse about Australia's environment held that the only way to avoid catastrophic fires was to do frequent controlled burns across the entire landscape. This new discourse was dubbed the "Australian strategy," because Australia was the first major industrialized nation to adopt it. The Australian strategy contrasted with the United States' continued adherence to the fire suppression discourse. Thus it fit nicely with Australians' desire to highlight the distinctiveness of their environment and way of life.

Starting in the 1970s, a new discourse challenged the "Australian strategy." Environmentalists argued that frequent burning was detrimental to many species, who needed a much longer interval between fires to survive. Where the Australian strategy saw Australian ecosystems as resilient to disturbances or even dependent on them, the new environmentalist discourse presented these ecosystems as more fragile and vulnerable to human interference. Rather than the "proof" of a major event in which the prevailing discourse failed to work, the environmentalist discourse rested its justification on the authority of ecological science.

The conflicting discourses were thrown into higher relief by the "Black Saturday" fires of 2009 (Figure 3). This series of fires was the most catastrophic and deadly in Australia's history (Teague et al. 2010). For some people, these fires only confirmed the validity of the old discourses. For example, one major faction argued that the fires were so destructive because fire services had given in to the environmentalists and stopped doing enough controlled burning. If the commitment to the Australian strategy were renewed, these people said, the environment would once again be successfully managed. One version of the environmentalist discourse, meanwhile, shifted its scale to take a broader view. It's not just human interference in the fire cycle through too-frequent controlled burns that's the problem -- it's also human interference in the larger climate system. According to these people, climate change had caused record temperatures and droughts, creating conditions under which no amount of controlled burning could tame the inevitable inferno. The only solution, then, was to increase efforts in Australia and worldwide to stop climate change. Another discourse held that fire catastrophes were now inevitable. Attempts to stop the fires would be a waste of effort. Instead, people should simply abandon homes in high-risk areas, or failing that, build shelters in which they could survive the next firestorm.

To evaluate which of these discourses is the best one would require a lengthy investigation of the evidence that is beyond the scope of this chapter. But we know enough to outline the way we could look for a solution. Consistent with pragmatism, we would aim to figure out which discourse would enable Australians to live a valuable way of life given their environmental conditions. And consistent with Grid-Group Cultural Theory, we would be hesitant to assume that one discourse had all the answers and the others would never have anything to contribute.

Works Cited [link]

Collins, Paul. 2006. Burn: The Epic Story of Bushfire in Australia. Crows Nest NSW: Allen and Unwin.

Dewey, John. 1958. Experience and Nature. La Salle, Ill: Open Court Pub. Co.

Douglas, Mary, and Steven Ney. 1998. Missing Persons: A Critique of the Social Sciences. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Douglas, Mary, Michael Thompson, and Marco Verweij. 2003. Is time running out? the case of global warming. Daedalus 132 (2): 98-107.

Dryzek, John S., and Jeffrey Berejikian. 1993. Reconstructive democratic theory. American Political Science Review 87 (1): 48-60.

Fairhead, James, and Melissa Leach. 1995. False forest history, complicit social analysis: rethinking some West African environmental narratives. World Development 23 (6): 1023-1035.

Ingold, Tim. 2000. The Perception of the Environment: Essays on Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. New York: Routledge.

Pyne, Stephen J. 1991. Burning Bush: A Fire History of Australia. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

Roe, Emery. 1994. Narrative Policy Analysis: Theory and Practice. Durham: Duke University Press.

Teague, Bernard, Ronald McLeod, and Susan Pascoe. 2010. 2009 Victorian Bushfires Royal Commission Final Report.

Thompson, Michael. 1997. Security and solidarity: an anti-reductionist framework for thinking about the relationship between us and the rest of nature. Geographical Journal 163 (2): 141-149.

Thompson, Michael, Richard Ellis, and Aaron Wildavsky. 1990. Cultural Theory. Boulder: Westview Press.